Marcel Duchamp 1887-1968

Anne Sanouillet and Marcel Duchamp, New York, 1963

Perhaps no 1 was less dogmatically dadaist, yet more than spiritually dada, than Marcel Duchamp. While the dada-surrealist explosion was for many the catalytic agent of a discovery -- for example, for the prime movers of the review Littérature -- and was for so many others a suspension which gave them a literary life rather cheaply, information technology is evident that, through dada and surrealism, Duchamp has remained himself. His interior evolution, begun even before cubism, bears the mark of no known influence. In Duchamp are joined the essential elements of the dada defection: a full absence of principles or prejudices, things moveover being equal and permitted. "There is no solution," says Duchamp, "because there isn't any problem." This sense of "umor" is dada, equally well equally the amore for puns and spoonerisms which are then perfectly suited to transcending the comic. "My irony," says Duchamp, "is that of indifference: meta-irony."

Michel Sanouillet, The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, 1989

In society to view a big number of videos and slideshows on Duchamp, meet Dada Movies.

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

Earlier Marcel Duchamp, a work of art was an artefact, a concrete object. After Duchamp it was an idea, a concept. Duchamp did to art what Einstein did to physics and Darwin to religion: each destroyed the foundations of a discipline – although they did so in very different ways. Einstein thought long and hard until he formulated his new vision of the physical earth. Darwin agonised for decades, making himself physically ill, before announcing that we were merely members of the animal kingdom. In stark contrast, Duchamp approached the demolition of the art establishment and the pretentiousness of artists with the cold-eyed calculation of a saboteur looking for the all-time target. He found his target in New York in 1917.

Early on life

Henri Robert Marcel Duchamp was born in Blainville-Crevon in the Seine-Maritime province of upper Normandy on 28th July 1887. His mother Lucie (née Nicolle) was the daughter of a painter and engraver, and his father Eugene a local notary. The art of his maternal granddaddy filled their house, and the young Marcel and his iii surviving siblings absorbed artistic sensibilities from infancy. All four children took upwards fine art. Marcel became a painter; i elderberry brother Jacques a painter and printmaker; his other older brother Raymond became a very distinguished sculptor; and their young sis Suzanne another painter.

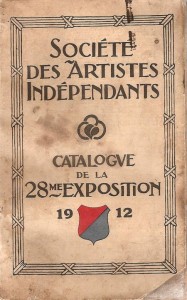

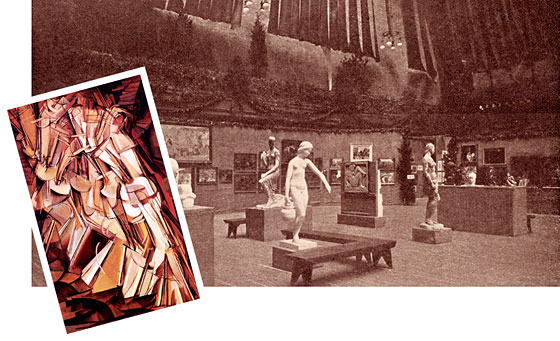

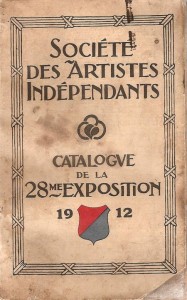

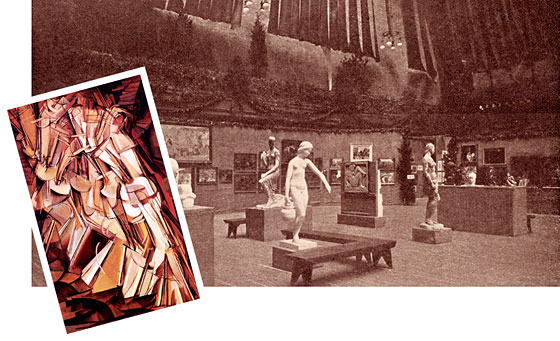

After winning a prestigious prize for cartoon at schoolhouse, Marcel decided to follow his elder brothers and study at the Académie Julian. Helped by the patronage of Jacques, who had go a member of the Académie Royale, he exhibited in the 1908 Salon d'Automne, condign a lifelong friend of the artist Francis Picabia and the critic Guillaume Apollinaire. Duchamp's cursory career as a pure painter culminated with his masterpiece Nude Descending a Staircase (now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art), which was submitted to the Cubist Salon des Indépendents in 1912. The organisers of that exhibition asked his elder brothers to persuade him to withdraw the painting or to paint over its title. He promptly went to the showroom in a taxi and removed it from the exhibition. This was a turning signal in his life, which he thereafter largely devoted to seeking an answer to two questions: What is to be deemed acceptable as art? and Who decides?

After gaining exemption from military service, Duchamp felt increasingly uncomfortable in France, and in 1915 decided to immigrate to the United states of america. Several of his paintings had been purchased in that location, so he could afford to move. On arriving he found he was a celebrity there, and he fabricated it his domicile, eventually taking citizenship in 1955.

Fountain

Duchamp had two strategic objectives. First, to destroy the hegemony exerted by an institution which claimed the right to make up one's mind what was, and what was not, to be deemed a work of art. Second, to puncture the pretentious claims of those who called themselves artists and in doing so causeless that they possessed extraordinary skills and unique gifts of discrimination and sense of taste. Tactically he sought to make a very bold, and very public, gesture, by seeking to submit some totally outrageous entry nether weather the art establishment would be forced either to accept under their own rules, or to break these rules, giving reasons for rejection. He saw the perfect opportunity in an exhibition planned past the Guild of Independent Artists in New York in April 1917. He was a fellow member of the committee, whose rules explicitly stated that all works submitted would be exhibited. This aimed to exist the biggest upshot of its kind, having 2,500 works submitted by1,500 artists, and so would attract the kind of attending Duchamp sought.

On 17 Apr, 1917 he discovered an ideal showroom when strolling along Fifth Avenue in the company of Walter Arensberg, his patron, a collector, and Joseph Stella, a fellow artist. When they passed the retail outlet of J.Fifty. Mott (now alas no longer there), Duchamp was fascinated past a brandish of sanitary ware. He had found what he had been diligently seeking; and persuaded Arensberg to purchase a standard, flat-backed white porcelain urinal. Taking it to his studio, he placed information technology on its back, signed it with the pseudonym "R.Mutt", and gave information technology the name Fountain. It is the but submission to the exhibition which is now remembered, since after having been on brandish for a short while, the organising committee, suitably outraged, rejected it.

However, his shrewd two-way bet had succeeded across Duchamp's wildest expectations, and he achieved the notoriety he was afterwards, and subsequently seismically shifted the thinking of the art world. In 2004, a panel of artists and art historians voted Fountain as the most influential artwork of the Twentieth Century. Duchamp'due south identify in the history of Art was commemorated in 2000 by the founding of the Prix Marcel Duchamp – an annual honor given to young artists by the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. That a tribute to his work should be associated with a edifice which its builder turned inside out would have profoundly appealed to Duchamp.

The original Fountain has disappeared, although a photograph exists, and seventeen copies exist in diverse fine art galleries.

The Philosophical Aftermath

Over the centuries, hundreds of artists take produced thousands of accepted masterpieces which adorn museums and galleries worldwide. Until the early Twentieth Century it had seemed fairly articulate what these works had in mutual: they were all physical artefacts such as paintings, sculptures, engravings, and etchings, which showed exemplary craftsmanship and were representations considered beautiful, interesting or inspiring. Today it seems that anything goes in fine art galleries: animal carcasses; unmade beds; comic book paintings; huge statues of Disney characters; rows of bricks; live performances; created landscapes – whatever. Information technology would exist totally unreasonable to claim that such a dramatic change could exist laid at the feet of ane man. It would every bit unreasonable to ignore the bear on made by Duchamp. It also seems ill-advised to merits, as the philosopher Arthur Danto in one case did, that this change ways that art is now dead. On the reverse, art seems to be flourishing as never before.

What has happened is that at that place has been a progressive demolition of practically all the conditions which had been regarded as mandatory for something to be considered a work of art. Art no longer has to represent anything, nor fifty-fifty to be beautiful (although of course it tin can exist), nor require exemplary skill for its production (although that might be so, besides). Neither does it have to be fabricated by the putative creative person, who can simply put forward an idea for somebody else to make or perform. Why one should then exist regarded every bit an artist, and the other not, is an interesting philosophical question in itself. Another question – very pressing if you've only spent a fortune on a Picasso – is, if it were possible to brand exact concrete copies (as soon may be the case using high-fidelity 3D printing), why should simply the original be a work of art?

It cannot be the case that absolutely anything can be a work of art, since then everything would be a piece of work of art. The real problem – and this is Duchamp's great legacy to philosophy – is that nosotros now demand to piece of work out a sufficient set of conditions for fine art. Several philosophers rose and are rising to this challenge. Nelson Goodman sought to treat all manifestations of art – painting, sculpture, music, literature, functioning and trip the light fantastic – in terms of a full general theory of symbols – thus examining the languages of art. As mentioned, Arthur Danto set out to establish that art was dead; so changed his mind, explaining why this in fact is not the case. What does certainly seem to be dead are old fashioned philosophies of aesthetics.

Although an accomplished and versatile artist, Duchamp'south contribution to philosophy has proved greater than his contribution to art. Art requires our left brains and our correct brains to talk to each other, and then give significant to experiences which lie beyond the grasp of reason. Exactly how this works and what its limits are (if any) poses philosophical issues of keen relevance, importance and difficulty, whose solutions would bring a greater breadth and balance to our cultural life.

Last Words

During the 1920s and 30s, Duchamp became a chess master and an authority on the game. For the residual of his life this passion excluded most other activities. When his wife left him, finally unable to cope with his obsessive personality, she made an appropriately powerful gesture, glueing his favourite pieces to his favourite board. Duchamp must take felt that at least this showed a sound grasp of one sufficient condition for the product of a work of fine art: she had made a telling statement without using words.

Marcel Duchamp died on 2nd October 1968 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, and was buried in Rouen Cemetery. On his tombstone he had arranged for an engraving: "D'ailleurs, c'est toujours les autres qui meurent" ("Anyway, it'southward always the others who dice"). In and then doing he had, almost fittingly, made his memorial both a philosophical argument and a work of fine art.

© Sir Alistair MacFarlane 2015

Sir Alistair MacFarlane is a former Vice-President of the Regal Society and a retired university Vice-Chancellor.

Philosophy Now - June-July 2015

Duchamp and His Toilet

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp, a French émigré residing in America, submitted an upside-down toilet for an art bear witness held by the Social club of Contained Artists in New York. He signed this piece 'R. Mutt' and placed information technology backside a transparent screen. His objective was to challenge previous notions of what constitutes art. This piece, in 2004, was voted the virtually influential modern artwork of all time past a console of 500 experts.

At get-go, some critics understandably thought Duchamp's toilet was a practical joke. Indeed, some people still struggle to take it seriously. Yet this iconoclastic piece was submitted as a challenge to the art world and has influenced artists ever since. Without Duchamp'south Fountain - Fountain being its legitimate name, although I prefer to call it 'toilet' - one couldn't imagine what a modernistic art exhibition would look similar.

There is no dubiousness that a stroll through a modernistic art exhibition can exist a dizzying experience. Ane's eye sockets will no dubiousness ache due to the constant eye rolls that these exhibitions seem to provoke. Furthermore, i volition probably have to toil through a whole lot of pretentious bullshit before one arrives at annihilation of artistic merit. Mod art is daze-provoking, ostentatious and in many means, just apparently onetime mad. I suppose this madness is what certain people detect and so irritating - or, in my case, so enjoyable - about the modern fine art world.

What is it that I discover so enjoyable virtually modernistic art? Well, if you get to London's national gallery and view the artworks of Turner or Constable, you might marvel at the draughtsmanship of the artist and the aesthetic entreatment of the piece of work. And this tin can exist, and oftentimes is, a wholly pleasurable experience. However, this kind of art museum, with its assortment of often all-too-familiar works, can likewise exist, cartel I say, ho-hum.

A modern art museum, on the other hand, with all its enigmatic conceptual art and information technology's seemingly pointless everyday-objects-turned-sculptures, can be a frightening and flummoxing experience, just never really boring. People seem to despise the lack of sense that is so apparent in modern and contemporary art but, for me, that lack of sense is the most exciting part. I love walking into a room with a looping video of a daughter picking her nose and then shouting 'hate' at the top of her lungs. I enjoy looking at a pile of boxes and trying, and failing, to work out what exactly this work represents. I adore the crazed, maniacal operation artists dancing on summit of marmalade while simultaneously whipping themselves while a discombobulated crowd looks on. The madness intrigues me.

Duchamp and his little conduce of antagonistic dadas wanted art to be a purely intellectual tool. Well, plenty of modern fine art, and certainly contemporary art, asks the audition to seek meaning from ostensibly nonsensical pieces and, for me, this is exciting and very rarely tiresome. And isn't it wonderfully advisable that all the ostensible madness of mod and contemporary art can be traced back to an industrially manufactured object that men would usually urinate in - turned upside down, of course.

Ioan Marc Jones in The Huffington Post - March 29, 2015

The Readymade Is Already Made

Of the twentieth-century art gods (Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol), Marcel Duchamp elicits no middle road. He is either revered as a godlike figure of contemporary art or disdained equally a charlatan. Curators, artists, critics and dealers praise his import in reframing and redefining what is art and how we view it. In fact, the other night at a dinner political party seated amongst a oversupply of the aforementioned art-earth folk, I asked, "Are we done with Duchamp?" Knives and forks dropped from their fingers as their eyes shot daggers at me. The rebuttal that followed began, " Nosotros tin never be washed with Duchamp!" and "If y'all know anything about gimmicky art, how can y'all advise such a question?"

Indeed, I swear, on a stack of Artforums, I am no fine art historian or art scholar, nor a curator, critic or dealer. I am simply and purely an art appreciator. And, I realize by proposing that I see an overuse of art proclaiming a Duchampian lineage or ideal that I am certain to provoke strong opinions from people smarter than I. What has this idealism washed for art? The ideal form, the ideal textile, the platonic expression, the ideal truth; these things continue to exist sought, but alas, they have all been institute!

They have all been found in everyday materials (which seems to exist the popular medium used in gimmicky art), such as trash, used clothing, packaging supplies, broken article of furniture and other multitudes of mundane objects thrown together is cast out in the galleries as "Duchampian." Marcel Duchamp influenced contemporary artists maybe more than any other master from the twentieth century. He paved the way for pop art, environmental fine art, assemblage, installation art and conceptual art. Even and then, Duchamp is overdone in contemporary art. Art historian and critic Barbara Rose, in her well-written commodity for The Brooklyn Track reviewing the contempo exhibition of Duchamp's paintings at Eye Pompidou, commented in her mail service script: "What Duchamp himself had done was ever interesting and provocative. What was done in his name, on the other hand, was responsible for some of the silliest, most inane, most vulgar non-art still being produced by ignorant and lazy artists whose thinking stops with the idea of putting a institute object in a museum." Bravo! I completely agree. This is what I am asserting when I ask, are we done with Duchamp? The products that call themselves works of art copying ideas and images put forth previously are far too numerous, too sporadic and have been done once again and again. Duchamp, past contrast, was compelled or obsessed to not fall into complacency or predictability; he challenged himself to non repeat and reuse the same thing. He disliked reproduction and secondhand experience.

From his failures, rebellion or both, Duchamp emerged successful. He failed at fine art school, in printmaking and with painting. Yet, he was non deterred. He could have changed class, pursuing a life equally a chess-playing librarian, but he didn't. He connected to question, "What is fine art?" and "How do we come across art?" In both life and fine art, he looked beyond what had already been done, rejected conventional conformity and avoided an affiliation with any group -- thus, non challenge to be a cubist, dadaist, modernist, surrealist, of futurist, yet associating with all. He felt it unnecessary to encumber his life with attachments and stated that he chose to live with or without "too much weight, with a wife [although, he was twice married], children, a country house, an automobile." He was a champion of independent thinking. An evasive, individual, elusive man and frequently known every bit a poker-faced trickster, he was a controversial figure with contradictions. [...]

Katherine Meadowcroft in Huffpost Arts & Civilization - March ten, 2015

Marcel Duchamp: a riotous A-Z of his surreptitious life

The iconic artist had a mortal dread of hair, posed as a cheese merchant to outfox the Nazis – and made artworks out of sperm. Here'due south a dictionary of Duchamp past Thomas Girst

(see Recent Books on Dada)

Artist

'I don't believe in art. I believe in the artist.'

Wheel wheel

The original Bicycle Bike readymade from 1913, and a second version, were lost. The third has a curious story. In 1995, a man walked into New York's MoMA and stole the tertiary version from the gallery. The thief left the building unnoticed, then returned the artwork the next day by throwing it over the wall of the sculpture garden.

Breasts

Duchamp used ane,000 foam-rubber breasts for the catalogue covers of the Paris exhibition Le Surréalisme in 1947. The back covers read 'Prière de toucher', or 'Please bear upon'.

Cheese

During the second world war, Duchamp devised a scheme to transport his artistic materials out of Europe. On the mode to the US, he passed through Nazi checkpoints in Paris posing equally a cheese merchant. Luckily, he did not arouse suspicion.

Chess

The game occupied him so much that, out of jealousy, his first wife, Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor, glued his chess pieces to the board. The marriage lasted seven months. [...]

theguardian.com, Mon seven Apr 2014

MARCEL DUCHAMP - Periodical Entries by Marvin Lazarus, 1959 - 1960

Dada Perfume: A Duchamp Interview

Making Mischief: Dada Invades New York at the Whitney through February 23, 1996

by John Perrault

One-time but good.

Putting modern art on the map

Volition Gompertz

The story of modern art is in many ways the story of the 20th century. Art shaped and was shaped by events, people, ideas and innovations far beyond the narrow confines of its globe. The modern skyscrapers of Manhattan, TS Eliot, Monty Python, the Sex Pistols, the iPhone and the great political, philosophical and social movements of the concluding hundred years all owe something to the art produced by Manet, Monet and those pioneering artists who followed in their wake. [...]

But there is perhaps one person in a higher place all others whose influence and personality boss 21st-century artistic activity and disquisitional thinking – an individual who was able to impose his will on the globe without recourse to courtship the media, condign a glory, or having vast amounts of money. Information technology is an incredible story within a story that starts on 2 Apr 1917; on this day, the American president, Woodrow Wilson, was on his anxiety in Washington DC urging Congress to make a formal announcement of war on Germany – a historic and earth-changing moment.

Meanwhile, in New York City, three well-dressed, youngish men had emerged from a smart duplex apartment at 33 West 67th Street and were heading out into the metropolis. They were oblivious to Wilson's exhortations, just as they were to the fact that their afternoon stroll would as well have epoch-making consequences on a global scale. Fine art was about to alter for e'er.

The 3 friends walked and talked and smiled, occasionally breaking into restrained laughter. For the elegant Frenchman in the centre, flanked past his two stockier American companions, such excursions were always welcome. He was an artist who had non yet lived in the city for two years: long plenty to know his style effectually, too brusk a time to have go blasé about its exciting, sensuous charms. The thrill of walking southwards through Central Park and downward towards Columbus Circle never failed to lift his spirits; the spectacular sight of copse morphing into buildings was, to him, ane of the wonders of the world.

The trio ambled downwards Broadway. Equally they approached midtown the sun disappeared behind impenetrable blocks of concrete and glass, bringing a leap arctic to the air. The two Americans talked across their friend, whose hair was swept back exposing a high forehead and well-divers hairline. As they talked he idea. As they walked he stopped. He looked into the window of a store selling household goods and raised his hands, cupping his eyes to eliminate the reflection in the glass, revealing long fingers each of which was crowned with a perfectly manicured boom.

The intermission was cursory. He moved away from the storefront and looked up. His friends had gone. He glanced around, shrugged, lit a cigarette and crossed the road – not to find his companions, but to seek the dominicus'south warmth. It was at present four.50pm, and a wave of anxiety washed over the Frenchman. Soon the stores would be closed and there was something he desperately needed to buy.

He walked a little faster. Someone shouted his name. He looked up. It was Walter Arensberg, the shorter of his ii friends, who had supported the Frenchman's artistic endeavours in America most from the moment he stepped off the boat on a windy June morning in 1915. Arensberg was beckoning him to cantankerous back over the road, by Madison Square and on to Fifth Avenue. But the notary's son from Normandy had tilted his caput upwards, his attention focused on an enormous physical wedge. The Flatiron Building had absorbed the French creative person long before he arrived in New York, an early on calling card from a city that he would go on to make his dwelling.

His initial encounter with the high-ascension edifice had come when it was start built and he was however living in Paris. He had seen a photograph of the 22-floor skyscraper taken by Alfred Stieglitz in 1903 and reproduced in a French mag. Now, 14 years later, both the Flatiron and Stieglitz, an American photographer-cum-gallery possessor, had become function of his new-world life.

Arensberg chosen again, this fourth dimension with a little frustration in his voice. The other man in their party laughed. Joseph Stella was an artist too. He understood his Gallic friend's precise still wayward heed and appreciated his helplessness when confronted by an object of involvement.

United over again, the three fabricated their fashion southward until they reached 118 5th Avenue, the retail premises of JL Mott Iron Works, a plumbing specialist. Inside, Arensberg and Stella chatted, while their friend ferreted around among the bathrooms and doorhandles that were on display. Afterwards a few minutes he called the store assistant over and pointed to an unexceptional, apartment-backed, white porcelain urinal. A Bedfordshire, the young lad said. The Frenchman nodded, Stella raised an eyebrow, and Arensberg, with an exuberant slap on the banana's back, said he'd purchase it.

Fountain / Fontaine (1917 - 1964) In 2004, this urinal was voted the unmarried most influential piece of art in the 20th century.

They left the store. Arensberg and Stella called a taxi while the quiet, philosophical Frenchman remained on the sidewalk property the heavy urinal. He was amused by the plan he had hatched for this porcelain pissotière, which he intended to use as a prank to upset the stuffy American fine art crowd. Looking downwards at its shiny white surface, Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) smiled to himself: he thought it might cause a fleck of a stir.

Duchamp took the urinal back to his studio, laid it down on its back and rotated it 180 degrees. He so signed and dated it in black paint on the left-hand side of its outer rim, using the pseudonym R Mutt 1917. His work was nigh done. There was only ane job remaining: he needed to give his urinal a proper name. He chose Fountain. What had been, just a few hours before, a nondescript, ubiquitous urinal was at present, past dint of Duchamp'southward actions, a work of fine art.

At least information technology was in Duchamp's mind. He believed he had invented a new grade of sculpture: 1 where an artist could select any pre-existing mass-produced object with no obvious aesthetic merit, and by freeing it from its functional purpose – in other words making it useless – and by giving it a proper noun and changing its context, turn information technology into a de facto artwork. He called this new form of fine art a readymade: a sculpture that was already fabricated.

His intention was to enter Fountain into the 1917 Independents Exhibition, the largest bear witness of modern art that had e'er been mounted in the Us. The exhibition itself was a challenge to America's fine art institution. It was organised by the Society of Independent Artists, a grouping of costless-thinking, forwards-looking intellectuals who were making a stand against what they perceived to be the National Academy of Design's conservative and stifling attitude to modern art (just as the impressionists had done in a very similar style over 40 years earlier).

They alleged that whatsoever artist could become a member of their society for the price of $ane, and that whatever member could enter upward to ii works into the 1917 Independents Exhibition as long equally they paid an additional charge of $5 per artwork. Duchamp was a director of the society and a member of the exhibition'southward organising committee. Which, at to the lowest degree in part, explains why he chose a pseudonym for his mischievous entry. Then again, information technology was Duchamp's nature to play on words, make jokes and poke fun at the pompous art world.

The name Mutt is a play on Mott, the store from which he bought the urinal. It is likewise said to be a reference to the daily comic strip Mutt and Jeff, which had first been published in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1907 with just a single character, A Mutt. Mutt was entirely motivated by greed, a dim-witted spiv with a compulsion to chance and develop ill-conceived get-rich-quick schemes. Jeff, his gullible sidekick, was an inmate of a mental asylum. Given that Duchamp probably intended Fountain to be a critique of greedy, speculative collectors, it is an interpretation that would appear plausible. Equally does the proffer that the initial R stands for Richard, a French colloquialism for moneybags. With Duchamp nada was e'er simple; he was, subsequently all, a homo who preferred chess to fine art.

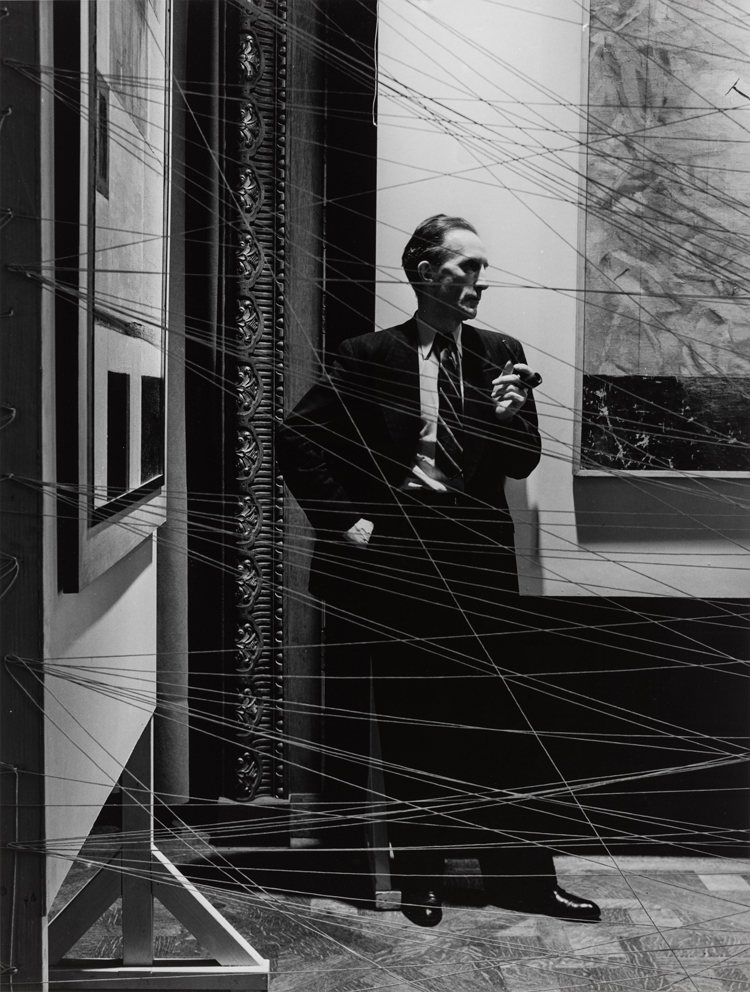

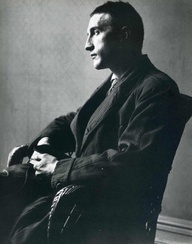

Marcel Duchamp by Man Ray

Duchamp had other targets in mind when selecting a urinal as a readymade sculpture. He wanted to question the very notion of what constituted a piece of work of fine art every bit decreed by academics and critics, whom he saw every bit the cocky-elected and largely unqualified arbiters of taste. His position was that if an creative person said something was a work of art, having influenced its context and meaning, then it was a work of art, or at least demanded to be judged every bit such. He realised that although this was a fairly simple suggestion to grasp, it would revolutionise art if accepted.

Until this bespeak, the medium – canvass, marble, forest or stone – had dictated to an artist how he or she could go about making a work of art. The medium ever came first, and only then would the creative person be allowed to project his or her ideas on to it via painting, sculpting or drawing. Duchamp wanted to flip the bureaucracy. He considered the medium to be secondary: get-go and foremost was the thought. Fine art could be constructed from, and mediated through, annihilation. That was a large idea.

The hidden meanings independent within Fountain don't stop in Duchamp's wordplay and provocation. He specifically chose a urinal because equally an object information technology has plenty to say, much of it erotic, an attribute of life that Duchamp frequently explored in his piece of work. It doesn't, for example, take much imagination to come across its sexual connotations when presented upside down. That allusion may or may non have been understood by those who sat alongside Duchamp on the organising commission; either mode his co-directors were unimpressed. Fountain was rejected and banned from the 1917 Independents Exhibition. The feeling among the majority of the lodge'south advisers (in that location were some, including Arensberg and Duchamp, who argued passionately in its favour) was that Mr Mutt was taking the piss.

Which of class he was. Duchamp was challenging his fellow lodge directors and the organisation'southward constitution, which he had helped to write. He was daring them to realise the idea that they had collectively set out, which was to accept on the fine art establishment and the authoritarian voice of the conservative National Academy of Design with a new liberal, progressive set of principles. The conservatives won the boxing, but as we now know, spectacularly lost the war. R Mutt's exhibit was deemed too offensive and vulgar on the grounds that it was a urinal, a subject that was non considered a suitable topic for discussion amidst America'south puritan center classes. Team Duchamp immediately resigned from the board. Fountain was never seen in public, or ever again. Nobody knows what happened to the Frenchman's pseudonymous piece of work. It has been suggested that it was smashed past 1 of the disgusted committee, thus solving the problem of whether to testify it or not. Then again, a couple of days afterwards, at his 291 gallery, Stieglitz took a photograph of the notorious object, just that might take been a hastily remade version of the readymade. That also has disappeared.

But the corking power of ideas is that you lot cannot uninvent them. The Stieglitz photograph was crucial. Having Fountain photographed by one of the art world'due south most respected practitioners, who as well happened to run an influential gallery in Manhattan, was of import. It was an endorsement of the work by the avant garde, and provided a photographic record: documentary proof of the object's existence. No matter how many times the naysayers smashed Duchamp's piece of work, he could become back down to JL Mott's, buy a new one and simply copy the layout of the R Mutt signature from Stieglitz'southward image. And that's exactly what happened. In that location are 15 Duchamp-endorsed copies of Fountain to be found in collections effectually the world.

When i of those copies is put on display information technology is weird to see people taking it so seriously. You see hordes of earnest exhibition visitors craning their heads around the object, staring at it for ages, standing back, looking at information technology from all angles. It's a urinal! It's non even the original. The art is in the idea, not the object.

The reverence with which Fountain is now treated would have amused Duchamp, who chose it specifically for its lack of artful appeal (something he chosen anti-retinal). The original readymade sculpture was really only ever intended as a provocative prank, but has gone on to go perhaps the single most influential artwork of the 20th century. The ideas it embodied direct influenced several major art movements, including dada, surrealism, abstract expressionism, popular fine art and conceptualism. Duchamp is unquestionably the nigh revered and referenced artist amidst today'southward contemporary artists, from Jeff Koons to Ai Weiwei. [...]

guardian.co.uk, Friday 24 August 2012 21.35 BST

Marcel Duchamp - 1917

Dada was an extreme protest against the physical side of painting. It was a metaphysical attitude. It was intimately and consciously involved with 'literature.' It was a sort of nihilism to which I am still very sympathetic. It was a manner to get out of a country of mind--to avoid existence influenced past i'due south firsthand environment, or by the past: to go abroad from cliches—to get free. The 'blank' force of dada was very salutary. Information technology told you 'don't forget you are non quite so "blank" as you think yous are.' Usually a painter confesses he has his landmarks. He goes from landmark to landmark. Really he is a slave to landmarks—even to contemporary ones.

Dada was very serviceable equally a purgative. And I retrieve I was thoroughly witting of this at the time and of a desire to effect a purgation in myself. I recall certain conversations with Picabia along these lines. He had more intelligence than nigh of our contemporaries. The rest were either for or against Cézanne. There was no thought of anything beyond the physical side of painting. No notion of freedom was taught.

Marcel Duchamp, in The Museum of Modern Fine art Bulletin, New York: The Museum of Modern Fine art, 1946.

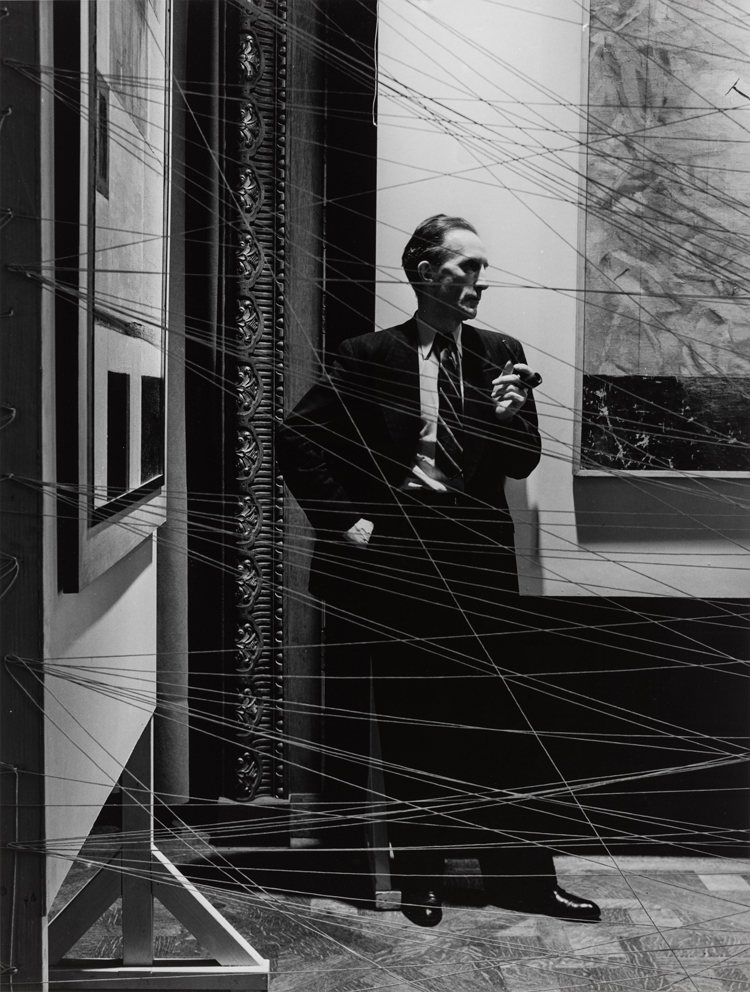

Marcel Duchamp in 1942 by Arnold Newman

With Duchamp, the clues are in the string and shadows that envelop the artist in Newman's 1942 photo. Taken at a landmark art exhibit called "Beginning Papers of Surrealism", the image puts Duchamp backside the layers of twine that Duchamp had strung throughout the show at a large Manhattan mansion. Dressed in conform and necktie, hand in his pocket, Duchamp is looking away, with shadows covering his cheek and even his eyes. Nosotros see Duchamp but can't meet him.

Newman, who meticulously researched his subjects, knew that Duchamp opposed art that appealed only to the visual senses. Duchamp disliked painting for painting's sake. Duchamp's famous "readymades" — like the urinal he exhibited in 1917 — were meant to detach artgoers' reliance on an object'due south looks, and to stoke internal reactions. Newman, who studied painting on scholarship at the University of Miami, understood Duchamp's "anti-retinal" principles, which were at odds with much of the art establishment.

Jonathan Curiel in SF Weekly - December 9, 2014

An interview with Marcel Duchamp

Ii years before Marcel Duchamp's death in 1968, the Belgian director, Jean Antoine, filmed an interview with the artist in his Neuilly studio in the summer of 1966.

Apart from beingness circulate on Belgian telly, the interview has been shown several times to the mainly educatee audience of the association, but the text has never been published.

This transcript, edited for The Art Newspaper, is the nigh faithful rendering possible of the manner Marcel Duchamp expressed himself. It is a remarkable document that gives us a fresh and immediate insight into his heed.

more

Teeny and Marcel by Man Ray - 1955

Marcel Duchamp at 125

In celebration of the 125th ceremony of Marcel Duchamp'southward birth - he was born in Normandy on July 28, 1887 - we await back at curator Joan Rothfuss' essay on the Dadaist provocateur from our 2005 publication, Bits & Pieces Put Together To Nowadays A Semblance Of A Whole: Walker Art Center Collections.

Among the most radical aspects of Marcel Duchamp's practice - which is a fountainhead in the history of twentieth-century art - was his insistence that the about interesting fine art springs from a nimble mind rather than a skilled mitt. Operating out of a spirit of serious play he used chance techniques and quasi-mechanical processes to create his works, sidestepping the personal and the handmade.

He made and then many variations, versions, and replicas of his objects that conventional distinctions between "original" and "reproduction" collapse like a house of cards. This activity was taken to its logical limits in his notorious "readymades" functional objects without aesthetic pretension (such as a urinal), which he simply purchased and designated as his artwork (and which, today, exist just every bit copies, since all the "original" readymades have been lost). Duchamp's work developed alongside and against the formal explorations of Cubism, clearing an alternate conceptual path that has been followed by artists from Jasper Johns to members of Fluxus to Robert Gober.

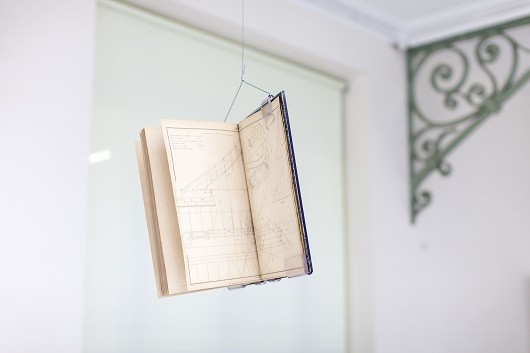

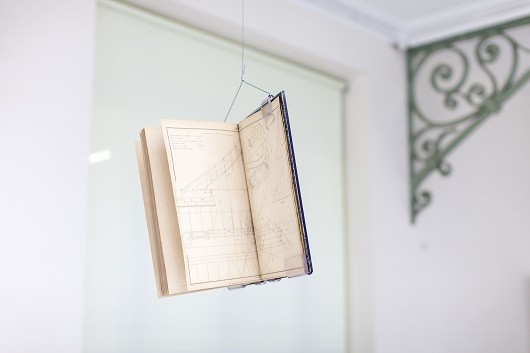

In 1935 Duchamp wrote to a patron that he was thinking of making "an anthology of approximately all the things I produced." The next yr he embarked on the project, which lasted more than than xxx years, and produced virtually 300 albums containing dozens of two– and three-–dimensional reproductions of his works an artist'south version of a salesman's sample kit. The albums, which he titled De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy), are similar miniature retrospectives of his career in personal, portable museums. When opened, the box becomes architectural, with three vertical "walls" and a "floor," and its unbound contents can be examined in any order the viewer wishes. The reproductions were supervised past Duchamp but made past others, using techniques (such as collotype, a labor-intensive process used to reproduce photographs) that reside somewhere between the mechanical and the handmade.

La Boîte-en-valise, 1936-1941/1968

Authorship is confused past the work'south ambiguous attribution (to either Duchamp or his modify ego, Rrose Sélavy), and we are even given two ways to think about its creation: the passive "from" and the active "by." This piece of work is ofttimes cited as the catalyst for artists' burgeoning interesting in multiples during the 1960s, and it certainly inspired Fluxus artist George Maciunas to create unorthodox anthologies like the Fluxkit, which was packaged in a briefcase. Although fabricated in multiple copies, such works were non seen every bit secondary documents. Every bit Duchamp noted drily in 1952, "Everything important that I have done can be put into a petty suitcase."

Joan Rothfuss in Walker Mag (July 25, 2012)

Marcel Duchamp biography on WikiArtis

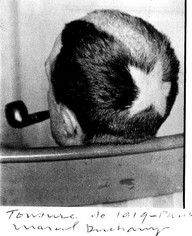

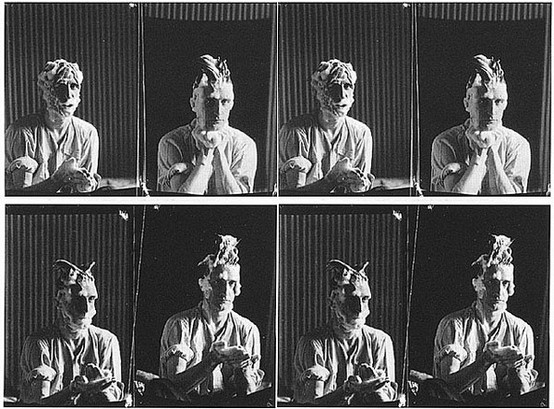

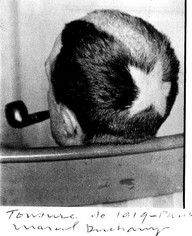

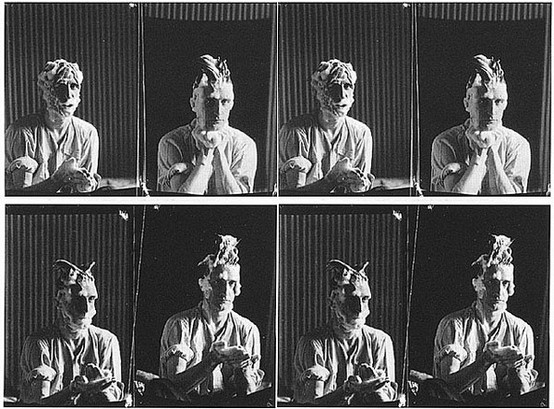

Tonsure . Photograph by Homo Ray - 1919

Some Ready-mades by Marcel Duchamp

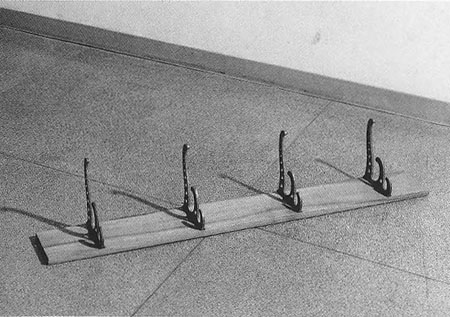

Bottle-rack - Porte-bouteilles (1914/1964)

Hidden Noise / A bruit surreptitious

In Accelerate of the Broken Arm

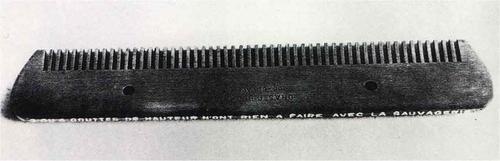

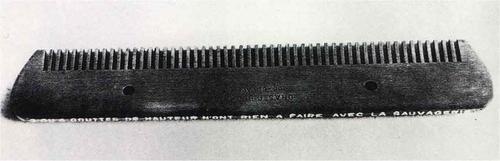

Comb / Peigne - 1916: "Quelques gouttes de hauteur n'ont rien à faire avec la sauvagerie"

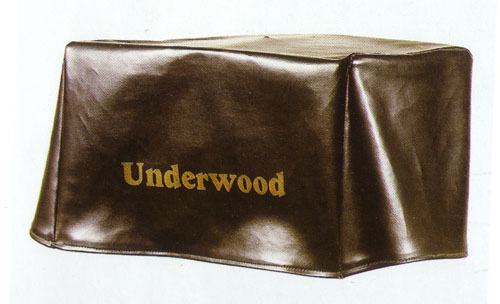

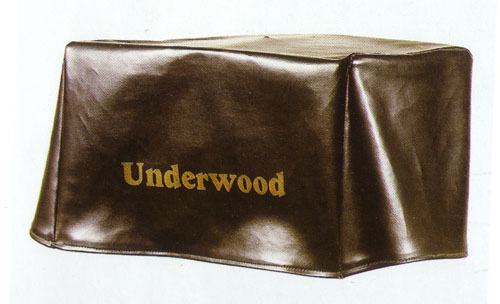

Underwood

Unhappy ready-fabricated/Ready-made malheureux

Marcus MOORE: Marcel Duchamp: "Twisting Memory for the Fun of It" or a Form of Retroactive Interference? — Recalling the Impacts of Leaving Home on the Ready-made

In the 1960s, Marcel Duchamp, arguably the most influential artist of the twentieth-century, came into real prominence and unprecedented fame. During this menstruation he gave many interviews in which he frequently took a capricious stance. 1 topic was crucial: his comments concerning the origin of readymade works of fine art— mass-produced everyday objects that he first selected in 1913-1914 in Paris, and then after leaving in 1915 to New York he located other examples.

In interviews he referred to the ready-made as "a happy idea, just as material objects they signify and embody Duchamp's leaving domicile. When leaving home, an individual works through an acculturation process during which they are never truly settled. This article considers the fate of material objects in relation to the veracity of Duchamp'south memory 50 years after the fact in the 1960s, a time when the artist was also the progenitor of a postmodern position.

Some of Duchamp'southward Works

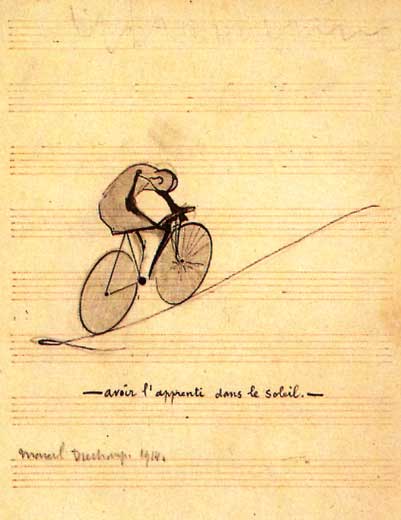

Bicycle Wheel - Roue de bicyclette (1913/1964)

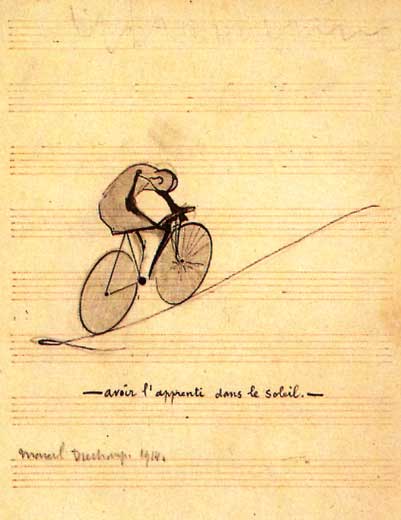

To Take the Apprentice in the Sun / Avoir l'apprenti dans le soleil - 1914

The recurrent bike theme...

Elena Filipovic:

A Museum That is Not

Ane could say that everything begins and ends in Marcel Duchamp's studio. His first New York studio is perhaps best known from a series of small and grainy photos, some of them out of focus. They were taken former between 1916 and 1918 by a certain Henri-Pierre Roché, a good friend of Duchamp. Roché was a writer, not a professional photographer, clearly. He was the same guy who would go on to write Jules et Jim, arguably a far ameliorate novel than these are photographs. Only their aesthetic quality was non really what mattered. Duchamp was fastened to those little pictures. He kept them and went back to them years subsequently, working on them and then leaving them out for us like his laundry in the picture. Or like clues in a detective novel.

more

Elena Filipovic is a writer and independent curator. She was co-curator, with Adam Szymczyk, of the 5th Berlin Biennial, When things cast no shadow (2008) and co-edited The Manifesta Decade: Debates on Gimmicky Fine art Exhibitions and Biennials in Post-Wall Europe (2006). Recently she curated the get-go major solo exhibition of Marcel Duchamp's piece of work in Latin America, at the Museu de Arte Moderna in São Paolo and the Fundacion Proa in Buenos Aires (2008-2009). She is tutor of theory/exhibition history at De Appel postgraduate curatorial training programme and advisor at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. She is also currently invitee curator of the Satellite Plan of the Jeu de Paume in Paris for 2009-2010 and is completing a PhD at Princeton University on Marcel Duchamp's exhibition and installation practice.

Sophie Stévance - Les opérations musicales mentales de Duchamp. De la "musique en creux"

Duchampian Images

(Marcel Duchamp World Community)

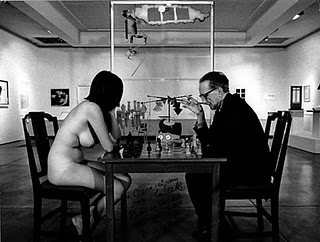

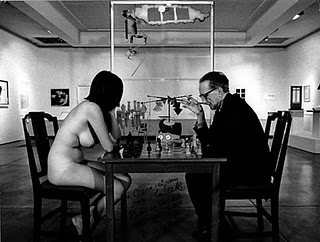

Marcel Plays Chess in Pasadena

Photo : Julian Wasser

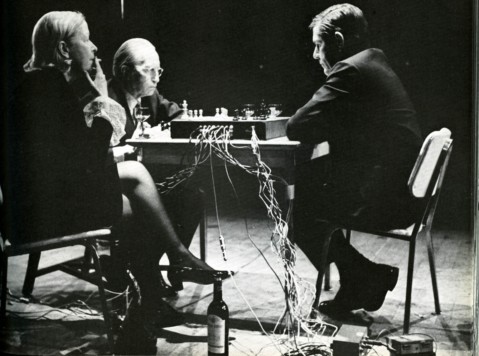

Photo of the chess match between a very properly dressed Marcel Duchamp and a nude Eve Babitz at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1963. She was taking her revenge for not having been invited to the inauguration of the exhibition. Not but had Duchamp attended the famous 1913 premiere of Igor Stravinsky's Rite of Spring in Paris, which had caused a anarchism, but the artist's immature, buxom chess opponent was the daughter of Sol Babitz (a violinist who was a co-founder of the "Early Music Laboratory") and a k-daughter of Stravinsky. Duchamp checkmated Eve at every game while discussing The Firebird at the aforementioned fourth dimension.

Eve Babitz on Being Photographed Nude with Marcel Duchamp

[...] O.K., let'south start with the Duchamp photograph: you lot, 20, naked, playing chess with him, 76, fully clothed. Eve, I have to tell you, that is one seriously boobalicious bod yous've got going on there. I mean, hubba hubba.

Yes, I know. I'chiliad normally a 36 double D. Only that was the in one case in my life I was on nascency-control pills. My breasts blew up. They wouldn't fit into any of my dresses. And they, y'all know, they hurt. But they were —well, I thought they should exist photographed, really.

How come?

So they were immortalized.

Because they were something else?

Yes. That'due south right.

And you were doing all this to make your married beau [Walter Hopps] jealous, right?

Mm-hmm. Yep. Walter was groovy. He was the closest I ever got to the Jewish doctor that my grandmother e'er hoped I'd ally. [...]

past Lili Anolik in Vanity Off-white, Fabruary v, 2014

MoMA | The Collection | Marcel Duchamp

About xxx of Duchamp's works.

Cocky Portrait (1958)

From Notes on the Infra-Slim

a transformer designed to use the slight, wasted energies such as:

the excess of pressure level on an electric switch

the exhalation of tobacco smoke

the growth of hair, of other body pilus and of the nails

the fall of urine or excrement

movements of fear, astonishment, boredom, anger

laughter

dropping of tears

demonstrative gestures of hand, feet, nervous ticks

forbidding glances

falling over with surprise

stretching, yawning, sneezing

ordinary spitting and of claret

vomiting

ejaculation

unruly hair, cowlicks

the sound of nose-blowing, snoring

fainting

whistling, singing

sighs, etc [...]

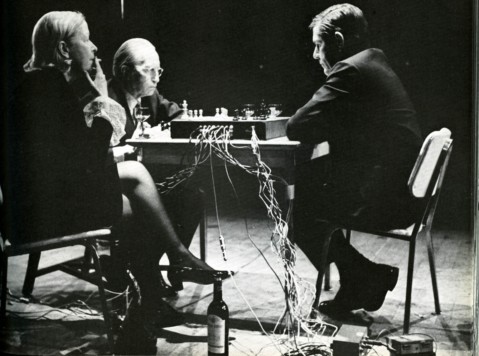

Marcel Duchamp - John Muzzle: Reunion

Actually, Cage hadn't lost every unmarried lucifer with Duchamp. There was one that he definitely won, later a manner. It happened in Toronto, in 1968. Cage had invited Duchamp and Teeny to be with him on the stage. All they had to do was play chess as usual, but the chessboard was wired and each motion activated or cut off the sound coming live from several musicians (David Tudor was one of them). They played until the room emptied. Without a give-and-take said, Cage had managed to turn the chess game (Duchamp'south ostensive refusal to work) into a working performance. And the performance was a musical slice. In pataphysical terms, Cage had provided an imaginary solution to a nonexistent problem: whether life was superior to fine art. Playing chess that night extended life into fine art –or vice versa. All it took was plugging in their brains to a set of instruments, converting nerve signals into sounds. Optics became ears, moves music. Reunion was the name of the slice. It happened to exist their endgame.

John J. McNulty

Teeny Duchamp, Marcel Duchamp and John Cage in Toronto, March 5, 1968

Reunion: John Muzzle, Marcel Duchamp, Electronic Music and Chess

The year 1999 marks the thirty-offset anniversary of Reunion, a performance in which games of chess determined the course and acoustical ambience of a musical event. The concert—held at the Ryerson Theatre in Toronto, Canada— began at eight:thirty on the evening of 5 March 1968, and concluded at approximately i:00 the next morning. Main players were John Muzzle, who conceived (but did not actually "compose") the work; Marcel Duchamp and his wife Alexina (Teeny); and composers David Behrman, Gordon Mumma, David Tudor and I, who also designed and synthetic the electronic chessboard, completing information technology just the night before the performance. Except for a brief mantle call with Merce Cunningham and Dance Company in Buffalo, NY the following calendar month, Duchamp made his last public appearance in the part of chess master— in Reunion.

Misconceptions

In the intervening 31 years, more fiction than fact regarding Reunion has appeared in documents well-nigh Cage and Duchamp, even from the pens of authors with prestigious reputations. Nicolas Slonimsky wrote in the 1978 edition of Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians: He [Cage] also became interested in chess and played demonstration games with Marcel Duchamps [sic], the famous painter turned chessmaster, on chessboards designed by Lowell Cross to operate on aleatory principles with the assist of a computer and a organisation of laser rays.

Past Lowell Cross

"Three Infinitesimal Wonder" past Mike Figgis. Must-see video on and about Duchamp's "Fountain".

Information technology's definitely true that some things are funnier in English than they are in French and vice versa. I mean Duchamp was very well enlightened of this. Certain of his puns are totally untranslatable. Or they may be translatable just they withal don't have the impact in translation because there'll exist a nuance, a nuance or maybe only through French usage that will non translate or will be not come across.

Photo of M.D. past Duane Michals - 1964

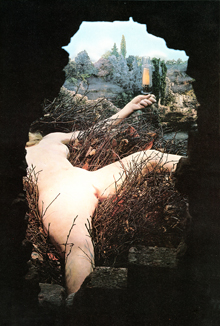

William N. Copley and Marcel Duchamp

Copley'south relationships with the surrealists were some of the well-nigh of import and formative on his development equally a person and an artist. He remained shut friends with René Magritte, Man Ray, Max Ernst, and of course Marcel Duchamp. Marcel Duchamp died on October 2, 1968. He had been living primarily in New York since Copley met him in 1947. Copley was a frequent company to Duchamp's studio on Fourteenth Street once he returned to New York afterward his years in French republic. Upon Duchamp's death The William and Noma Copley Foundation (later the Cassandra Foundation) gave Marcel Duchamp's last piece of work, "Etant Donnée" to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where it is withal on view. Copley had been one of the few people who knew that Duchamp was working on such a slice, and a major supporter of the piece of work. William Copley's moving obituary of Duchamp that appeared in the New York Times on October 13, 1968 reflects the importance that Marcel had in his life:

Because I knew him, I find it inconceivable to speak of Marcel Duchamp as no longer living. For those who missed the point of his greatest argument, he has not been among them since he officially ceased painting years agone. Though he did not die that long ago he did define eternity, and he entered immortality at the time he left the easel and took art with him into creative life.

Had he been unwilling to share the experience, this would take been a fulsome obituary- and this is not an obituary.

Rrose Sélavy (1921) past Man Ray. The proper name is a humorous pun on the words "Eros, c'est la vie", which means "Sexual practice, that's life".

L.H.O.O.Q.

Here is the story of this "work of art" : in 1919, at the tiptop of Dada activities in Paris, Duchamp took an inexpensive colour reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, enhanced her smile with a moustache and goatee, on which he pencilled five messages : 50.H.O.O.Q. (a pun -- "Elle a chaud au cul"), although Duchamp himself in one case politely translated it every bit "There is fire downwardly below".

Duchamp'southward fellow dada co-conspirator, Francis Picabia, hoped to publish it in his magazine 391, couldn't have waited for the artifact to come up back on fourth dimension from New York, so he himself drew the moustache on Mona Lisa but forgot the goatee! But Picabia wrote at the lesser "tableau Dada par Marcel Duchamp". Duchamp of course was the beginning one to notice the missing goatee and this became a subject for his teasing of his friend.

Some 20 years passed before he would be given the opportunity to rectify this omission. In the early 1940'due south, the original Picabia replica of L.H.O.O.Q. mysteriously resurfaced, plant in a bookstore by Jean Arp, another dada artist. Duchamp seized the opportunity to "consummate" the prototype by carefully adding in black ink the goatee and using a blue fountain pen to write "moustache par Picabia / barbiche par Marcel Duchamp / avril 1942".

Biography of Marcel Duchamp

by Jeffrey Shivar

The 1913 art exhibit that scandalized New York

The 1913 art exhibit that scandalized New York

Article in Ephemeral New York on the Armory Testify.

"Chaos at Armory Show" past Jerry Saltz

(published April 1, 2012 in New York Magazine)

Nude Descending the Staircase / Nu descendant l'escalier

Happy Birthday Eadweard Muybridge!

Interesting article + a brusque film about the lensman who perhaps inspired Duchamp's Nu descendant un escalier.

(April ix, 2012)

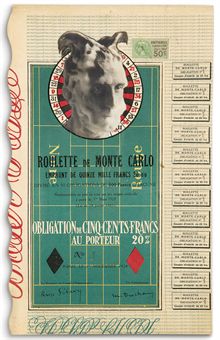

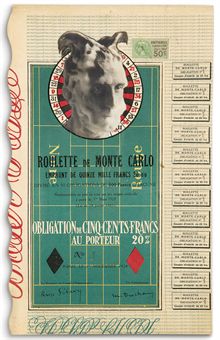

Miami Gallery Acquires Rare Marcel Duchamp Print

AffordableArt101 Fine Prints announced the acquisition of a rare lithograph past French artist Marcel Duchamp. Printed in 1938 and issued in Paris by the deluxe art revue "XXe Siecle", the slice is called "Monte Carlo Bond" and is also known equally "Obligation Monte Carlo". Measuring 12 1/2 x 9 inches, the lithograph shows the infamous portrait of Duchamp taken past photographer Man Ray, superimposed onto a roulette wheel, with a casino gaming table in the background. [...]

(November 14, 2012)

Man Ray - Portraits of Marcel Duchamp (1924)

Marcel Duchamp's Dandyism : The Dandy, The Flaneur and The Beginnings of Mass Culture in New York during the 1910s

Marcel Duchamp World Customs (MarcelDuchamp.Net)

The Marcel Duchamp World Community Web Site offers a neutral, unbiased, internet location for the meeting and exchange of ideas amongst the international community of people interested in Marcel Duchamp studies. The site welcomes news, events, publications, papers -- anything related to Marcel Duchamp and his larger circle of friends in Dada and Surrealism.

The Artworks of Marcel Duchamp

in xv themes + a biography on WahooArt (an infrequent site).

Dada without Duchamp / Duchamp without Dada

An intelligent and well documented article by professor Marjorie Perloff.

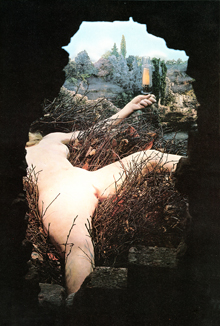

Encounter with Marcel Duchamp

Includes a reproduction and an explanation of Étant donné, the important dates in Duchamp'south life as well as other unpublished treasures.

Étant donnés (Given)

Étant Donné Marcel Duchamp

Étant Donné Marcel Duchamp

Presentation and table of contents of the excellent journal devoted to Duchamp, Étant Donné.

Marcel Duchamp and the Machine

by Alan Foljambe

An early example of Duchamp'southward attraction to machine grade is Chocolate Grinder.

Neuf Moules Mâlic, 1914-1915

Marcel Duchamp 'FOUNTAIN' - IS IT ART?

This is the second of four curt films made for Aqueduct four / Tate modern nearly modern and conceptual art. We took the art and put it in a unlike infinite or context and asked people to comment. In this episode nosotros took Marcel Duchamp's 'FOUNTAIN' and placed it in a public toilet. The mandatory, 'is it art' discussion followed!

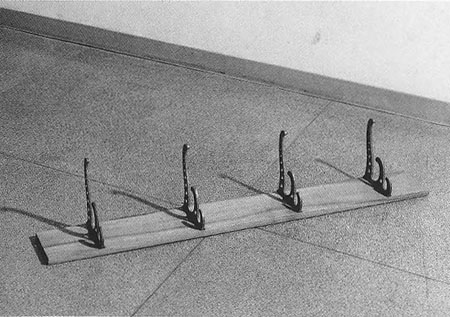

Trébuchet (Trap) - 1917

a coat rack the creative person ironically nailed to the flooring of his studio in reference to a critical chess position.

50 cc of Paris air - 1919

Philadelphia Museum of Fine art

Fresh Widow, 1920/1964

Constructed by a carpenter in accord with Marcel Duchamp's instructions, Fresh Widow is a small version of the double doors commonly called a French window. Duchamp was fascinated by themes of sight and perception; hither, the expectation of a view through windowpanes is thwarted by opaque black leather, which Duchamp insisted "be shined everyday like shoes." Windows had an of import place in the work of Duchamp, who stated, "I used the idea of the window to take a point of departure, every bit... I used a brush, or I used a form, a specific form of expression.... I could have made 20 windows with a dissimilar thought in each one...."

Puns and wordplay were likewise central to Duchamp'south work. By changing a few messages, Duchamp transforms "French window" -- which the work resembles in form— -- into "Fresh Widow," a reference to the recent abundance of widows of World War I fighters.

Rotoreliefs

Several editions were issued: 1935 Paris, 1953 New York, 1959 Paris, 1963 New York, 1965 Milan.

Prière de toucher, 1947

BRETON, André & DUCHAMP, Marcel (editors). Le surréalisme en 1947. Exposition du Surréalisme, présentée par André Breton. 139, (3) pp., 44 collotype plates with numerous illus., and 24 original prints hors texte: Lrg. 4to. Plain paper wraps.

Chemise: pinkish boards, mounted with a tinted foam-safe Readymade breast construction past Duchamp, encircled by a hand-trimmed blackness velvet cut-out.

"Back in New York, Duchamp came upward with an thought for the comprehend, which to a certain measure was derived from the collage he had made for the catalogue of the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition in 1942: a adult female'south bare breast encircled past a swath of black velvet cloth entitled "Prière de toucher" ("Please impact"). For the regular edition, a black-and-white photograph of this subject was prepared in accordance with Duchamp's instructions past Rémy Duval, a photographer from Rouen best known for a volume of nudes published in Paris in 1936. For the deluxe edition, actual foam prophylactic falsies were painted and glued to a pink paper-thin embrace by Duchamp with the assistance of the American painter Enrico Donati. 'By the end nosotros were fed up just we got the chore done,' Donati later recalled. 'I remarked that I never idea I would get tired of treatment so many breasts, and Marcel said, 'Peradventure that'southward the whole thought'" (Naumann). Paris (Pierre à Feu/ Maeght), 1947. $35,000.00 (Ars Libri)

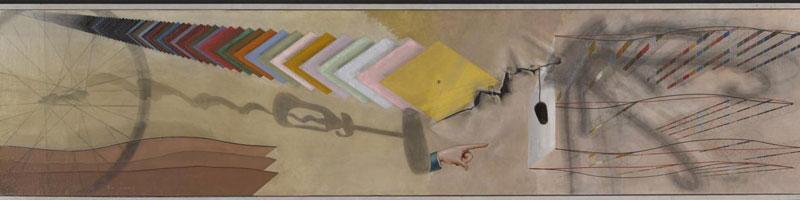

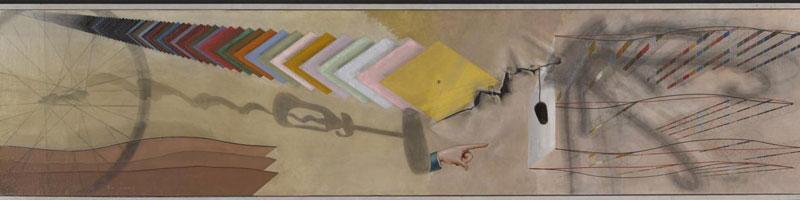

Marcel Duchamp's Tu m'

In 1918, after painting the work yous run across here, Marcel Duchamp, one of the three most influential artists of the 20th century -— the others existence Matisse and Picasso -— never painted over again.

What a affair to contemplate!

The picture, which is in the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery, was deputed from Duchamp by his wealthy patron, Katherine Dreier. Information technology is titled Tu yard', which is believed to be an abbreviation of "Tu m'embêtes" ("Yous bore me") or perchance fifty-fifty "Tu g'emmerdes" ("You give me the [expletive]."

The painting presents, in shadow course, a corkscrew, a hat rack, and a small inventory of Duchamp'south and so-called readymades, which he had been producing (if that is the right word —- perhaps simply "signing"?) since 1913.

There are besides three prophylactic pins stuck through a painted tear, a long bottle brush protruding from the moving picture at correct angles, a bolt, a human hand with a pointing finger that was painted by a professional sign painter, and a staggered series of paint color swatches. [...]

Past Sebastian Smee in The Boston Globe on Oct seven, 2014

Making Sense of Marcel Duchamp

Interactive blithe chronicle which brings to life the ideas and influences at the source of Duchamp's fine art.

Marcel Duchamp News - The New York Times

News most Marcel Duchamp, including commentary and archival articles published in The New York Times.

Witch's Cradle (1943)

Rare silent flick by Maya Deren with Marcel Duchamp.

Part i

Part 2

Lydie Sarazin-Levassor, The Marcel Duchamp I married

Her memoirs, published for the first time in Britain, portray a desperate liaison. Excerpts in The Independent, 11/02/08.

Bits & Bites

A website containing 9 superb photos of Marcel Duchamp or his works.

Marcel Duchamp on tumblr

An enormous if somewhat repetitive collection of Duchampiana.

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

The Allen Ginsberg Project

On the occasion of the 43rd anniversary of Duchamp's expiry, an fantabulous collection of interview footage and Duchampiana.

Was Marcel Duchamp the Anti-Creative person?

As an artist, Marcel Duchamp is difficult to classify – but he about certainly wanted it that way. During his career, just when anybody idea they knew what he was, a Cubist, for example, or a Surrealist, he switched to another style or no-style, left boondocks or the country or stopped being an creative person and went off and played chess in tournaments.

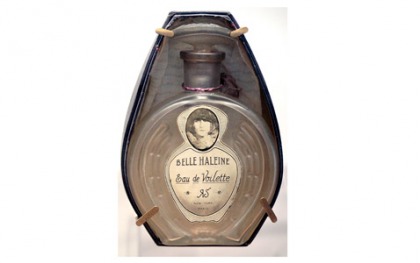

Duchamp would have been disgusted...

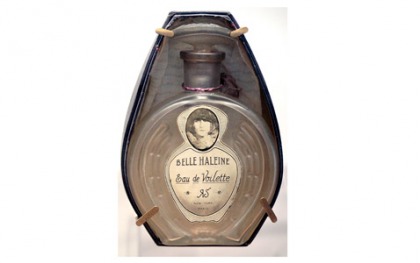

This bottle of perfume « Belle Haleine - Eau de Voilette » and its cardbord container signed Marcel Duchamp were sold at sale for 7,9 million euros to the public's applause.

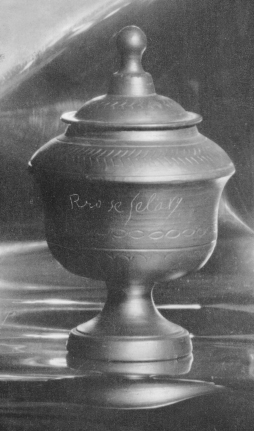

Duchamp's Terminal Ready-fabricated

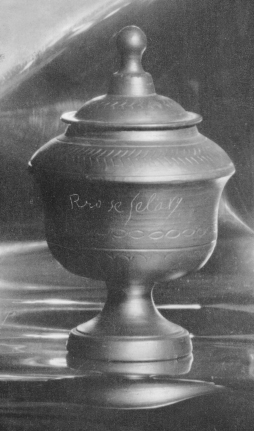

Marcel Duchamp flicked the ashes of his cigar into this urn during the Rrose Sélavy dinner on May fifteen, 1965. Click to run into the menu.

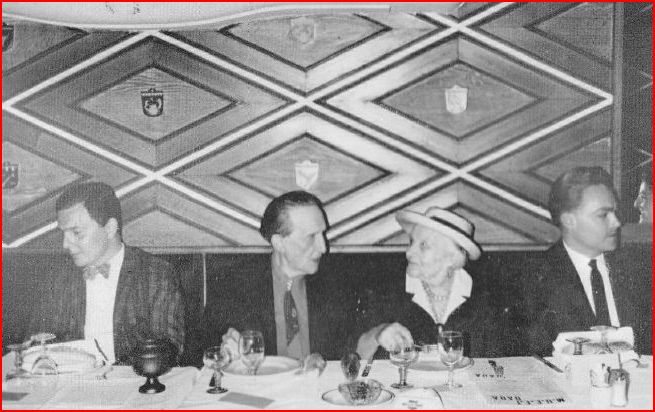

This photograph was on the inside cover of the first issue of the Revue de l'Clan pour l'Etude du Mouvement Dada (October 1965). The urn is a provoked set-made which contains Marcel Duchamp's ashes, fallen directly from his cigar during the Rrose Sélavy dinner which reunited 30 members of the association around Duchamp on Saturday, May fifteen, 1965 at the Victoria restaurant in Paris. Since the minutes recording the contents of the urn were read past the president, [Michel Sanouillet] and and so burned in the urn at Duchamp'south asking, its contents remain mysterious.

Among those present were, from left to right, Jacques Fraenkel (Théodore Fraenkel'southward nephew), Marcel Duchamp, Mme Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia and Rodrigo de Zayas (Marius de Zayas's son).

Photo Jampierre

The 1913 art exhibit that scandalized New York

The 1913 art exhibit that scandalized New York

Post a Comment for "As a Leader of the Dada Movement Marcel Duchamp Believed Art Should Appeal to the"